29 April, 2020

During the season of new shoots and blossoms, this month’s article investigates the vegetable gardens and crops grown in Holy Child schools and communities. It celebrates how the efforts of sisters, staff and pupils in these endeavors reflect Cornelia’s industrious spirit during the hardest of ordeals.

Eastertide brought many significant moments in Cornelia’s life. On Maundy Thursday 1836 in Rome, after Pierce’s abjuration on Palm Sunday, Cornelia and Pierce were confirmed by their friend Cardinal Weld. It was on the Tuesday of Easter Week 1844 that Cornelia went to live in a house within the grounds of the Trinità dei Monti during a more disconcerting sojourn in Rome. Two years on from entering the convent gates, Cornelia departed with Frank and Ady on 18th April, Easter Saturday, to travel to England. After 33 years of tending to the Society as it took root and flourished, Cornelia’s life ended on Easter Friday, 1879.1 In the spring of 1846 Cornelia prepared an early form of the SHCJ’s rule after experiencing many painful and still recent changes in her life. With the same fortitude in her last spring of 1879, Cornelia chose from nursery lists and planted cuttings for the kitchen garden of St Leonards. To Cornelia the little plants ‘seemed as they shot up in all their variety to be the very last image of the beauty of God’.

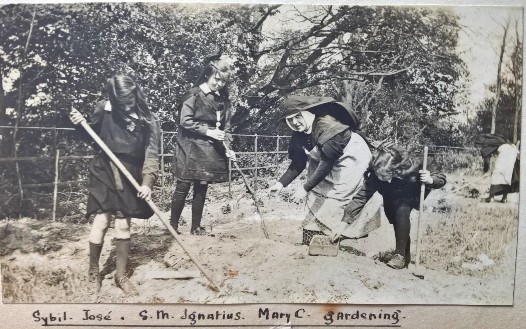

During ‘Easter or thereabouts’ in 1918, Mayfield’s Form V transformed a ‘grassy wilderness’ into allotments to grow vegetables as reported by Olga Davis. ‘Armed with spades, forks and hoes’ the girls dug trenches for potatoes and planted beans, radishes, cabbages and marrows. They were guided by their ‘head gardener’ Mother Mary Imelda from whom the girls were ‘eager to learn’. The ‘infertile-looking soil’ was blessed by Father Boniface on Ascension Day and the ground soon produced ‘large and luscious’ radishes. The girls even named the marrow plants they grew. The unfortunately named Job did not survive but Anthony was hoped to produce ‘numerous specimens of perfect marrowhood’ from which ‘delicious jam’ could be made with sugar rations saved by pupils during the holidays. The lettuces proved too tempting for Mother Mary Aquin’s ‘unscrupulous chickens’ who ‘simply looted’ them. Olga remarks ‘perhaps they thought we were food hoarding!’. Despite such setbacks, the girls looked forward to the satisfaction of digging potatoes and gathering beans for dinner.

A pupil in 1931 celebrates the rockery at Harrogate with its dwarf cypresses, yew trees and harebells protected by pieces of orange peel laid to ward off slugs and snails. She also praises the SHCJ nun whose efforts maintained the little garden:

Whatever is the weather,

M.M. St. Michael’s there,

She loves these plants most tenderly

And watches them with care.

Perhaps M.M. St Michael’s example inspired the more green-fingered pupils of Harrogate.

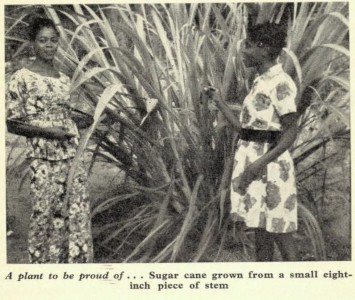

In 1966, a farm was started at Holy Child School, Cape Coast, Ghana. The first year of the farm was not without its challenges, with 500 of 503 egg plants killed by enblemma admota moths. In place of M. M. Aquin’s ‘unscrupulous chickens’, the Holy Child School farm had to contend with monkeys devouring every ‘lush, juicy kernel’ in their acre of corn. Tins that rattled when the wind blew were put up to keep the crafty mammals at bay. The farm continued through such difficulties to have a ‘first real harvest’ of plantain, pawpaw, red peppers and other vegetables which were brought to impoverished villagers at Queen Anne’s Point.

The farm diary kept by the Holy Child school, quoted in The Pylon, describes how ‘just to see the smiles on their faces was worth every bit of effort we have put into the farm’.4 Cornelia would no doubt have been proud to see how the Holy Child School ‘farmerettes’, through their persistence and problem solving, could make such a difference with the plants they grew.

Comments are closed.